EU Eastern Dimension

Moldova, a Romanian region in 25 years.

30 Nov 2010“In the next 25 years Romania and Moldova could be united again,” Romanian President Traian Basescu said in an article edited in Romanian newspaper Romania Libera. “EU borders will extend to the Dnestr River, and the democratic development in the region will be an incentive for other countries, such as Ukraine, to join the EU,” the president added. “The Balkans will become part of the EU and NATO within 25 years.”

La soluzione della crisi politica moldava appare ancora lontana. I risultati delle parlamentari non hanno assegnato chiare vittorie. Il Partito comunista, la formazione più votata, ha ottenuto 42 mandati contro i 43 precedenti, i liberal-democratici del premier Filat 32 (ne avevano 18), quello democratico dell’ex speaker Lupu 15 (13) e i liberali di Ghimpu 12 (15). Le altre 16 compagini che hanno partecipato al voto non hanno superato la barriera del 4%. L’affluenza alle urne si è attestata al 58,9%. All’estero hanno votato oltre 30mila moldavi, una decina erano i seggi aperti in Italia.

La coalizione liberale controlla 59 seggi su 101, 6 in più rispetto alle elezioni del luglio 2009. Ne mancano 2 per poter eleggere il presidente come vuole la Costituzione. Da oltre un anno e mezzo l’ex repubblica sovietica è senza il capo dello Stato ed in una situazione di paralisi istituzionale. La prima riunione del Parlamento, appena eletto, è prevista per dopo il 28 dicembre.

La tensione a Chisinau si taglia col coltello. Il leader dei comunisti Vladimir Voronin ha accusato i partiti al governo di avergli rubato il 10% dei voti. Senza un accordo tra i partiti non sembra possibile l’elezione del presidente e la fine di questa interminabile crisi.

Risultati

PC: 32,29%

PDLM: 29,38%

PDM: 12,72%

PL: 9,96%

Lista eletti

PCRM:

1. Voronin Vladimir, 1941, MP, president of the PCRM

2. Greceayii Zinaida, 1956, former Prime Minister

3. Muntean Iurie, 1972, economist, executive secretary of the PCRM

4. Postoico Maria, 1950, MP

5. Tkachuk Mark, 1966, MP

6. Dodon Igor, 1975, MP

7. Misin Vadim, 1945, MP

8. Vitiuc Vladimir, 1972, MP

9. Vlah Irina, 1974, MP

10. Petrenco Grigore, 1980, MP

11. Balmos Galina, 1961, MP

12. Zagorodnyi Anatolie, 1973, MP

13. Ivanov Violeta, 1967, MP

14. Sova Vasilii, 1959, MP

15. Sarbu Serghei, 1980, jurist

16. Domenti Oxana, 1972, MP

17. Chistruga Zinaida, 1954, MP

18. Gagauz Miron, 1954, MP

19. Panciuc Vasilii, 1949, mayor of Balti

20. Mironic Alla, 1941, teacher

21. Bannicov Alexandr, 1962, engineer

22. Poleanschi Mihail, 1980, anthropologist

23. Stati Sergiu, 1961, historian

24. Todua Zurab, 1963, historian

25. Gorila Anatolie, 1960, engineer

26. Bodnarenco Elena, 1965, MP

27. Staras Constantin, 1971, journalist

28. Bondari Veaceslav, 1960, expert in science of commodities

29. Abramciuc Veronica, 1958, MP

30. Reidman Oleg, 1952, MP

31. Musuc Eduard, 1975, MP

32. Eremciuc Vladimir, 1951, MP

33. Garizan Oleg, 1971, MP

34. Babenco Oleg, 1968, MP

35. Mandru Victor, 1059, MP

36. Filipov Serghei, 1965, doctor’s assistant

37. Reshetnikov Artur, 1975, former SIS director

38. Shupak Inna, 1984, anthropologist

39. Botnariuc Tatiana, 1967, MP

40. Petcov Alexandr, 1972, journalist

41. Popa Gheorghe, 1956, engineer

42. Anghel Gheorghe, 1959, jurist

The PLDM:

1. Filat Vlad, 1969, jurist, president of the PLDM, Premier

2. Tanase Alexandru, 1971, jurist, first vice president of the PLDM, Minister of Justice

3. Godea Mihai, 1974, historian, first vice president of the PLDM, MP

4. Palihovici Liliana, 1971, historian, vice president of the PLDM, MP

5. Leanca Iurie, 1963, Deputy Prime Minister, Minister of Foreign Affairs and European Integration

6. Belostencinic Grigore, 1960, economist, rector of the Academy of Economic Sciences

7. Hotineanu Vladimir, 1950, doctor, surgeon, Minister of Health

8. Juravschi Nicolae, 1964, chairman of the Olympic Committee

9. Tap Iurie, 1955, teacher, deputy Head of Parliament

10. Bolocan Lilia, 1972, teacher, AGEPI head

11. Ghiletchi Valeriu, 1960, MP

12. Sleahtitchi Mihai, 1956, MP, lecturer

13. Agache Angela, 1976, MP

14. Balan Ion, 1962, agronomist, MP

15. Deliu Tudor, 1955, MP

16. Ionita Veaceslav, 1973, MP, economist

17. Strelet Valeriu, 1970, jurist, historian, MP

18. Furdui Simion, 1963, historian, MP

19. Lucinschi Chiril, 1970, diplomat, businessman

20. Mocanu George, 1982, economist, head of the State Chancellery’s Local Administration Division

21. Cobzac Grigore, 1959, engineer, MP

22. Cimbriciuc Alexandru, 1968, jurist, MP

23. Butmalai Ion, 1964, jurist, MP

24. Ciobanu Ghenadie, 1957, teacher, composer, MP

25. Olaru Nicolae, 1958, MP

26. Ionas Ivan, 1956, engineer, MP

27. Plesca Nae-Simion, 1955, philologist, businessman

28. Dimitriu Anatolie, 1973, jurist

29. Ciobanu Maria, 1953, teacher

30. Vlah Petru, 1970, jurist, a member of the People’s Assembly of Gagauzia

31. Vacarciuc Andrei, 1952, head of Cimislia district

32. Stirbate Petru, 1960, doctor

The PD:

1. Lupu Marian, 1966, economist, MP, the president of the PDM

2. Plahotniuc Vladimir, 1966, engineer, businessman

3. Lazar Valeriu, 1968, Minister of Economy, vice president of the PDM

4. Corman Igor, 1969, historian, diplomat, vice president of the PDM

5. Diacov Dumitru, 1952, journalist, MP, president of honor of the PDM

6. Raducan Marcel, 1967, Minister of Construction and Regional Development

7. Candu Andrian, 1975, jurist, entrepreneur, director general

8. Buliga Valentina, 1961, Minister of Labor, Social Protection and Family

9. Filip Pavel, 1966, director general, SA Tutun-CTC

10. Botnari Vasile, 1975, economist

11. Stoianoglo Alexandru, 1967, MP

12. Apolschii Raisa, 1964, lawyer

13. Bolboceanu Iurie, 1959, unemployed

14. Guma Valeriu, 1964, economist, MP

15. Ghilas Anatolie, 1957, engineer, MP

The PL:

1. Ghimpu Mihai, 1951, jurist, chairman of the PL, Head of Parliament and Moldova’s Acting President

2. Salaru Anatolie, 1962, doctor, Minister of Transport

3. Fusu Corina, 1959, journalist, MP

4. Hadarca Ion, 1949, philologist, writer, MP

5. Munteanu Valeriu, 1980, jurist, MP

6. Bodrug Oleg, 1965, physician, editor, MP

7. Vieru Boris, 1957, philologist, MP

8. Lupan Vladimir, 1971, diplomat, physician, presidential adviser

9. Popa Victor, 1949, jurist, teacher at the Free International University

10. Cojocaru Vadim, 1961, economist, MP

11. Gutu Ana, 1962, philologist, MP

12. Brega Gheorghe, 1951, doctor, MP.

«В канун четвертых выборов президента вновь звучат уверения, что ключи от белорусской “президентции” лежат в Кремле. Белорусские избиратели с этим не согласны. И в целом демонстрируют все более проевропейские настроения».

Статья – БДГ Деловая Газета – Валерия Костюгова

BUCHAREST, Romania – Romania and Moldova signed a border treaty Monday, almost two decades after Moldova declared independence from the Soviet Union, Associated Press writes.

Romania’s Foreign Minister Teodor Baconschi and Moldova’s Prime Minister Vlad Filat emphasized the good co-operation between the neighbours, which has resulted in a number of new agreements being adopted in the past year since a pro-European alliance came to power. Romania supports Moldova’s current government. Monday’s signing took place ahead of a general election in Moldova on Nov. 28 in which the pro-European parties face the Communists who favour closer ties to Moscow.

Romania’s President Traian Basescu said last month that the treaty will disprove claims by Moldovan Communists that Romania has territorial claims on Moldova. This was echoed by Baconschi, who said that by signing the document “we also discourage the obsessive affirmations” of some Moldovan politicians who believe Romania has claims on Moldova. The treaty deals with technical issues such as the marking of the border, usage of water, railways and roads, fishing, hunting and breaches of the border regime.

Romania has been lobbying hard for closer ties between Moldova and the European Union, of which Romania is a member. Baconschi said Romania hopes that the border with Moldova will eventually become an internal border within the European Union.

European Commission President Jose Manuel Barroso has welcomed the signing of a border treaty, calling it “an excellent example” of regional cooperation. Bucharest has repeatedly refused to sign a bilateral political treaty with Moldova, most of which was part of Romania before World War II.

Romania was the first country to establish diplomatic relations with Moldova after the latter declared independence from the Soviet Union in August 1991. Romania’s President Traian Basescu had repeatedly stated that Bucharest shall never sign a treaty recognizing the consequences of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact and the secret additional protocol to it. However, the delicate pre-election situation in Moldova has finally changed Romania’s official stance on this issue.

Россия – ЕС, визовый режим в тупике.

30 Oct 2010«Людям визовый режим не нужен. И стремление его убрать — самый благородный политический проект путинского правления. Ведь чем больше простых россиян общается со “старухой Европой”, тем виднее им будут определенные преимущества живой демократии. Русские дипломаты твердят, что они хоть завтра готовы визовый режим снять. Но ничего не выходит. Не выйдет и через год, и даже через три…

Ведь для Европы этот безвизовый режим в разы менее нужен, чем для России. В прошлом году из 142 миллионов россиян 9,3 миллиона путешествовали в страны ЕС. А из 501 миллиона жителей ЕС в Россию въехали чуть более 5 млн….

В ЕС безвизовый режим действительно означает эту свободу. Путешественник может пересечь любую границу, гостить где и у кого хочет. А Россия? Ваше государство не доверяет иностранцам. Наверное, считает, как и раньше, что любой западник в России занимается тем, чем занималась на Западе Аня Чапман со товарищи….

И бюрократия строит барьеры, чтобы осложнить шпионам да диверсантам пребывание в России. Вы слышали о регистрации для иностранцев? Вроде бы безобидная формальность. Но на практике — великолепный способ отпугнуть чужаков: находясь в любой точке России более трех суток, гость должен найти или гостиницу, или хозяина (точнее, собственника) квартиры, который бы официально, на двух бланках, с целым букетом ксероксов и оригиналов, осведомит власти, что у него остановился нероссиянин. Да потом еще надо найти или офис иммиграционной службы или отделение почты, где это заявление примут. А если им там вдруг почерк не понравится — то все заново…»

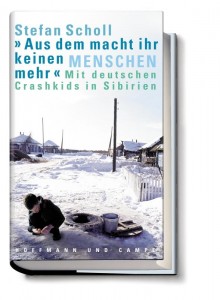

Статья – – Штефан Шолль – Московский Комсомолец № 25487 от 28 октября 2010 г.

Stefan Scholl Moskovskij Komsomolets

Aleksander Kwasniewski, former President of Poland and the Chairman of the YES Board. “You must have a clear picture what role you want to play in this globalised and versatile world. This should change your approach and the way you view things. Globalisation is a process we are not able to stop. We are tightly intertwined with it”.

1. The choice between the West and the East is not so important for Ukraine. “Every Ukrainian president has to find balance between Russia and the EU. The complication is what kind of balance should it be, how to define and describe it”.

2. Ukraine and Ukrainians must believe in their own strength and not to reject European prospects, because euro-integration of Ukraine is an objective demand of our time. “Ukrainians have to believe in their own power and future, because you have potential. We can discuss whether we need Turkey in EU for a long time. But at some moment we will ask the Turks to join the European Union. So, eventually the time will come when we will ask you, Ukrainians, to join the EU. we need you”.

At the same time this doesn’t calls off the need for reforms Ukraine must go through: “We have a lot of work to do. One has to solve problems and fulfill commitments. What is of great importance – you need to create civil society. You need nation’s activity, intelligent voter and intelligent electorate, which control the system and vote consciously”

YES, Yalta, October 2nd, 2010.

Il braccio di ferro tra maggioranza filo-europeista e minoranza comunista continua senza sosta. Il presidente ad interim e speaker del Parlamento Mihai Ghimpu ha annunciato di non voler sciogliere l’Assemblea legislativa se il referendum di riforma costituzionale del 5 settembre dovesse fallire. “Non voglio il caos – ha osservato il capo di Stato facente funzioni nel corso di un’intervista -. Servono le giuste condizioni per una tale scelta”. La Carta fondamentale indica, invece, nelle elezioni generali la soluzione a questo tipo di problemi.

L’ex presidente, nonché leader del Pc moldavo, Vladimir Voronin aveva lanciato, in precedenza, un appello agli elettori a boicottare la consultazione del 5 settembre che ha l’obiettivo di emendare la Costituzione in vigore. Se la proposta dei filo-europeisti passasse il capo dello Stato sarebbe eletto direttamente dal popolo e non dalla maggioranza dei deputati del Parlamento come è avvenuto in passato.

La crisi politica in Moldova dura dalle parlamentari del 5 aprile 2009. Allora il Pc ottenne 60 mandati, ma i filo-europeisti riuscirono a bloccare la nomina del capo dello Stato. Servivano 61 voti per scegliere il successore di Voronin. L’Alleanza per l’integrazione europea fece così sciogliere l’Assemblea legislativa in ottemperanza della Costituzione.

Le successive parlamentari del 19 luglio 2009 decretarono la vittoria dei 4 partiti filo-romeni con il Pc all’opposizione. La coalizione di governo conta 54 voti, mentre i comunisti 43, 4 sono gli indipendenti. Tutti i tentativi di eleggere un presidente sono finora falliti.

I filo-europeisti hanno intrapreso una dura politica anti-russa, che ha provocato un nuovo embargo da parte di Mosca del vino moldavo, principale risorsa della repubblica ex sovietica.

Quest’interminabile empasse politica rischia di mettere in serio pericolo la stessa esistenza del Paese, in cui elementi latini e slavi sono mischiati tra loro. Alcune forze spingono affinché la Moldova diventi una regione della Romania.

Newsweek magazine compiled a list of the 100 best countries in the world to live in according to 5 categories: health, economic dynamism, education, political environment and quality of life. Top 3 include Finland, Switzerland and Sweden.

Estonia ranks 32nd, Lithuania 34th and Latvia 36th. Ukraine takes the 49th place having outrun Russia 51st and Belarus 56th.

Burkina Faso, Nigeria and Cameroon are recognized to be the world worst countries.

Ennesimo litigio tra Mosca e Minsk con l’Europa a farne le spese. Chi tra i due contendenti abbia ora ragione non è facile stabilirlo. Gli uni pretendono il pagamento del gas consumato, gli altri quello dei diritti di transito.

Per ragioni politiche e geostrategiche, per oltre un decennio, il prezzo degli approvvigionamenti energetici russi a Minsk è stato di favore, quasi quello che pagano le regioni della Federazione. Su questo vantaggio non da poco, il presidente Lukashenko è riuscito ad evitare il crollo industriale-economico degli anni Novanta in Bielorussia e a dare stabilità al suo Paese.

Le cose sono cambiate dopo la “rivoluzione arancione” pro-occidentale in Ucraina nel 2004. Il Cremlino, attraverso la Gazprom, è passato all’incasso, provocando la rabbia di Lukashenko, che l’amministrazione Bush ha definito “l’ultimo dittatore” d’Europa. In sintesi, non più rapporti alla sovietica, quasi completamente basati sul barter, ma contatti pagati con soldi sonanti a prezzi di mercato o quasi.

La Bielorussia vive un momento particolare: il prossimo anno sono previste le elezioni presidenziali e l’economia ha subito i colpi della recessione internazionale. Lukashenko aveva chiesto di saldare alcuni pagamenti in macchinari, ma il collega Medvedev gli ha risposto pubblicamente in maniera considerata da Minsk sprezzante. “Scusate – ha evidenziato il leader bielorusso -, ma quando iniziano ad umiliarci noi ci offendiamo. Così non si deve permettere di comportarsi un presidente di un Paese amico, un presidente che dirige in pratica lo stesso popolo”.

Quindi se la Gazprom ha tagliato i rifornimenti del 30% fino all’85% del gas consegnato, Minsk ha colpito il “tallone d’Achille” russo, ossia ha sospeso il passaggio di gas russo verso ovest. Sul suo territorio transita, però, in realtà solo il 20% circa del totale degli approvvigionamenti al Vecchio Continente. E poiché uno dei due gasdotti, Jamal-Europa, è controllato dai russi la decisione di Minsk riguarda solo il 6,25% dei volumi totali all’Ue. I disagi saranno, perciò, minimi. Lukashenko ha un’arma spuntata, ma può dar fastidio lo stesso oggi. Sa perfettamente che i russi stanno costruendo un gasdotto sotto al Baltico insieme ai tedeschi, il Nord Stream, che verrà terminato nel 2011. La Bielorussia vedrà così la sua rilevanza strategica ridursi.

L’anno scorso i due Paesi fratelli si affrontarono nella guerra del petrolio con relativo blocco di oleodotti. Il contendere era il privilegio dei bielorussi di rivendere il greggio russo sul mercato internazionale senza pagare dazi a Mosca. Minsk, alla, fine fu costretta a cedere.

Ma gli screzi e le querelle non finiscono qui. Lukashenko è irritato dalla posizione egemone del Cremlino nella neo-nata Unione doganale (Russia, Bielorussia, Kazakhstan). Non gli è chiaro quali imposte verranno cancellate e a chi. Indirettamente si è reso conto che, dopo 16 anni di presidenza, Mosca lo vuole probabilmente scaricare se troverà un altro leader di sua fiducia. Al duo Medvedev-Putin non è piaciuto la concessione dell’asilo politico all’ex capo di Stato kirghiso Bakiev.

L’Unione europea si trova, pertanto, coinvolta in uno scontro altrui. Dare forza al suo programma “Partnership orientale” con Minsk sarà in futuro probabilmente l’unico modo per evitare sgradevoli sorprese.

Адам Михник: Польша, Россия и Восточная Европа.

21 Jun 201063-летний главный редактор крупнейшей польской “Газеты выборчей” Адам Михник:

«В российско-польских отношениях нет симметрии. Россия — великая держава. Польша — страна среднего масштаба в Евросоюзе. Все зависит от того, какие тенденции возобладают в Кремле».

«Партия братьев Качиньских до сих пор была партией национального страха, национального комплекса неполноценности, национальной угрозы. Их идеология сводилась к тому, что все против нас: и русские, и немцы».

«Коморовский? Он консерватор. Либеральный. Католик. Демократ. Ответственный. Стабильный. Нормальный. Но, хотя я буду за него голосовать, он не герой моего романа».

«Лично мне никакое примирение с Россией не нужно. Я всю жизнь считал себя антисоветским русофилом».

«В Польше уже нет истерического отношения к вашей стране. Но кое-что осталось в нашей подкорке. И если такие настроения целенаправленно подогревать, то все это можно разбудить снова — как, кстати, и антисемитизм, и германофобию. Нынешняя Польша — страна успеха»

«С моей точки зрения, присвоение Степану Бандере звания Героя Украины — огромная ошибка Ющенко». Однако «…героизация Бандеры — это не символ возврата нацизма. Это символ поиска Украиной своей национальной идентичности».

«Реальный вызов для России — это не Польша, не Америка и не Западная Европа. Западная цивилизация — это, напротив, ваш натуральный союзник. Ислам и Китай — вот в чем сегодня заключается реальный вызов для России».

Статья Михаил Ростовский Московский Комсомолец № 25378.

Mikhail Rostovsky Moskovskij Komsomolets

Welcome

We are a group of long experienced European journalists and intellectuals interested in international politics and culture. We would like to exchange our opinion on new Europe and Russia.

Categories

- Breaking News (11)

- CIS (129)

- Climate (2)

- Energy&Economy (115)

- EU Eastern Dimension (85)

- Euro 2012 – Sochi 2014 – World Cup 2018, Sport (43)

- Euro-Integration (135)

- History Culture (198)

- International Policy (261)

- Military (74)

- Interviews (18)

- Italy – Italia – Suisse (47)

- Odd Enough (10)

- Poland and Baltic States (126)

- Religion (31)

- Russia (421)

- Survey (4)

- Turning points (4)

- Ukraine (176)

- Российские страницы (113)

Archives

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- July 2019

- June 2019

- May 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- July 2018

- June 2018

- May 2018

- April 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- July 2017

- May 2017

- March 2017

- January 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- July 2016

- June 2016

- May 2016

- April 2016

- February 2016

- January 2016

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- June 2015

- April 2015

- March 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- December 2014

- November 2014

- October 2014

- September 2014

- August 2014

- July 2014

- June 2014

- May 2014

- April 2014

- March 2014

- February 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- November 2013

- October 2013

- September 2013

- August 2013

- July 2013

- June 2013

- May 2013

- April 2013

- March 2013

- February 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- October 2012

- September 2012

- August 2012

- July 2012

- June 2012

- May 2012

- April 2012

- March 2012

- February 2012

- January 2012

- December 2011

- November 2011

- October 2011

- September 2011

- August 2011

- July 2011

- June 2011

- May 2011

- April 2011

- March 2011

- February 2011

- January 2011

- December 2010

- November 2010

- October 2010

- September 2010

- August 2010

- July 2010

- June 2010

- May 2010

- April 2010

- March 2010

- February 2010

- January 2010

- December 2009

- November 2009

- October 2009

- September 2009

- August 2009

Our books